A CNC machinist is a highly skilled professional responsible for operating CNC machines that are used in the manufacturing industry to produce precision parts. Their day-to-day tasks are both varied and technical, and while it may seem like they simply push buttons to make a machine run, the reality is far more complex and detailed. In essence, their role requires a fusion of mechanical knowledge, computer programming, and an understanding of design nuances.

Programming and Setting Up Machines

A typical day for a CNC machist often starts with reviewing the blueprints or CAD (Computer-Aided Design) drawings provided by engineers or designers. These designs dictate the size, shape, and measurements of the part to be manufactured. Based on this information, the machinist must then decide on the most suitable tools, equipment, and processes for the job.

Once they’ve determined the right tools and methods, they begin the task of programming the CNC machine. This entails inputting a set of specific instructions that guide the machine on how to create the part. This code, often written in a language called G-code, instructs the machine on aspects like speed, direction, and depth for the tool to move. A single mistake in the programming phase can result in a faulty product, which emphasizes the precision and attention to detail required in this role.

Material Selection and Preparation

Having set up the CNC machine, the machinist now turns their attention to the material that will be used. The selection of the material is frequently determined by the intended use of the product, and the machinist must be well-informed about the characteristics and traits of various materials, ranging from metals such as aluminum and steel to other substances like plastics and composites.

Once selected, the material must be loaded onto the machine. Depending on the machine’s size and the piece’s dimensions, this can sometimes require the use of cranes or other lifting equipment. After it’s placed securely, the machinist must then set the starting point or “origin” for the machine. This is a crucial step, as it ensures the machine starts cutting from the right location on the material.

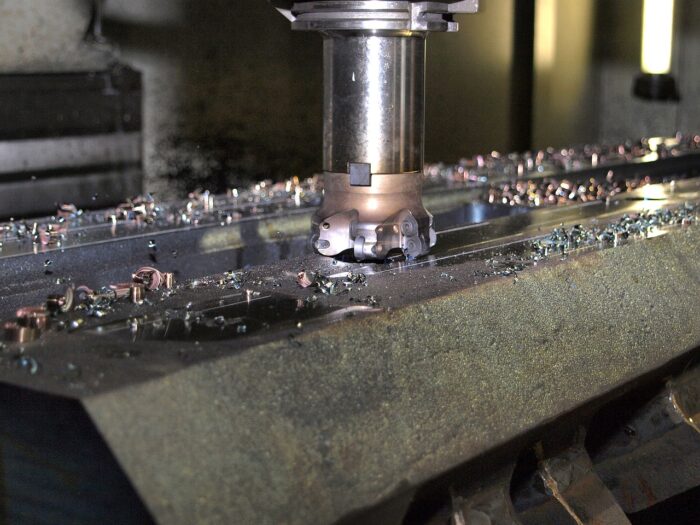

Machine Operation and Monitoring

After programming and material preparation, the CNC machinist can start the machine. However, their work doesn’t stop once the machine is in motion. Throughout the machining process, they have to closely monitor the operation. They must ensure that the machine is functioning properly, that the material is being cut as per the specifications, and that no unforeseen problems arise, like tool breakage or machine malfunctions.

Maintaining a keen eye on the process also allows the machinist to make real-time adjustments. Factors such as feed rate, speed, and tool path might need tweaking to get the desired outcome. To avoid overheating and minimize friction, cooling fluids or lubricants are frequently used. It’s the machinist’s duty to make sure they are applied correctly and effectively.

Quality Assurance and Post-Processing

Once the machine completes its task, the role of the CNC machinist shifts to quality assurance. This is a critical phase, as even a small deviation from the blueprint can make the part unusable. Apart from ensuring dimensional accuracy, machinists may also engage in post-processing activities. This could involve tasks like sanding, polishing, or applying finishes to the product. Sometimes, secondary operations on other machines, such as drilling or tapping holes, may also be required.

Maintenance and Troubleshooting

CNC machines, with their intricate parts and high operational demands, require regular maintenance. The CNC machinist is often at the forefront of this aspect, conducting routine checks and cleaning, replacing worn-out tools, and calibrating the machine as required. Proactive maintenance is crucial in this profession, given that machine interruptions can result in significant time and financial losses.

In addition to routine maintenance, machinists are also typically adept troubleshooters. When a machine malfunctions or produces sub-par results, they are tasked with identifying the cause of the problem. Whether it’s a software glitch, a misalignment, or a hardware issue, they need to be adept at quickly pinpointing and rectifying the issue to keep production lines moving smoothly.

Communication and Collaboration

A CNC machinist does not work in isolation. They collaborate with a team composed of engineers, designers, quality assurance experts, and other workshop staff. Effective communication and collaboration are essential in a machinist’s daily routine. Whether it’s discussing design specifications with an engineer, coordinating with quality control to ensure parts meet standards, or working alongside other machinists, clear communication and team synergy are key. Regular meetings might be held to discuss production schedules, project status, and problem-solving strategies.

Continuous Learning and Skill Development

New technologies, materials, and methodologies are frequently introduced, and a CNC machinist must stay abreast of these changes. Continuous learning, whether through formal training, workshops, or self-study, is part and parcel of a machinist’s career.

A machinist might be required to work on different machines within the same day or week. This demands adaptability and a willingness to continuously expand one’s skill set.

Documentation and Record Keeping

Proper documentation is essential in a CNC machinist’s daily routine. This can encompass everything from recording the details of machine setups, changes made during production runs, quality inspection results, and maintenance activities. Record-keeping also plays a crucial role in tracking the lifecycle of tools and machinery. Knowing when a tool was last replaced or when a machine was last serviced helps in planning future maintenance and ensures that everything is in optimal working condition.

Flexibility and Problem-Solving

A CNC machinist’s day is rarely monotonous. Unexpected challenges can arise at any moment, whether it’s a machine breakdown, a sudden change in project specifications, or an urgent rush order that needs to be fulfilled. The ability to adapt to these changing circumstances, think on one’s feet, and find effective solutions is an essential part of the job. A particular design might require unconventional machining techniques, or a recurring issue with a machine might necessitate a novel solution.